Bijli

Past

Nine years ago, during my second year of university, I came up with an idea to document all crime instances in Karachi. Muggings, target killing, bomb blasts were fairly regular at the time. It was called CityMap.

The teacher who taught the course that I built this app for, however, scared me off. He claimed that people behind the crimes wouldn't look lightly on this database, and by publishing this, I might put myself in danger. I was 20 at the time, and that was enough warning for me to back off.

A year later, much to my dismay, someone else built and published the app. It went massively viral, with almost 200k likes on Facebook by the time the anonymous creator abandoned the app.

For my final year project, I picked it up again. I added some cool new features; you could now navigate affected areas by looking at alternative routes and updates and navigation by text message. It was before cellular data became cheap in Pakistan, and everyone was either using SMS or BBM.

Back then, I hadn't started building mobile apps. So all this was for the web. I also created a small SMS API that would use an Android device to send out messages because I couldn't afford Twilio.

I got a good grade, and I forgot about CityMap (what an original name!), but the concept always stayed very dear.

Present

Fast forward to 2017. I had just left my job in Dubai and planned to settle back home when I realized that Karachi has many highly disruptive and frequent power outages. There isn't power for everyone, and the power companies deal with that by scheduling outages called load shedding. I'm not sure if it's a technique known outside of the country (or other similar countries).

I tried to find any schedules that the companies might have posted online to work around the outages. The plan was to do things that needed power when available, charge my devices, do npm install while there was power, and leave physical activities for the rest.

However, it turns out that some areas are more affected than others, and some places only have power for a few hours a day. Publicizing that data would be bad PR for the power companies, so nobody did it.

So I built Bijli.

It was a crowd-sourced app; people would drop a pin on a map when the power would go out in an area, and they'd get a notification an hour later asking if it's back now.

It went viral on Twitter and other local news. People loved it. I loved it because I wanted things to be more transparent and information more accessible. It's a theme with all my ideas/apps. Unfortunately, it wasn't sustainable.

Most people who reported power outages would forget about updating and go back to Netflix (I'm assuming) the moment power came back in their area. The concept was fresh, but the data was stale. Soon after, app ratings started dropping. The execution of phase one was a failure.

Phase two was ambitious. I tinkered with several ideas; two of them made (some?) sense.

While I'm not very familiar with hardware and have only tinkered with Raspberry Pi, the idea was to build some kits that would ping my APIs continuously unless they couldn't, which meant the power was out. I'd install these kits on power transformers all around the city.

I was excited by this approach, but it didn't pan out for several reasons.

- Building and maintaining the kits would be expensive

- The risk of sabotage or theft of said kits was high

- Possible legal implications of messing with public property

- Lack of real knowledge and experience with a large scale hardware deployment

The alternative was to get an API or some schedule from the power companies directly, which I could then map out in the app. That's when things got interesting.

I asked many people for their help; former classmates who were working at said power companies, contacts of my father's, people on Twitter to help me get in touch with the right people who could help me.

Initially, it was frustrating to see nobody else cared about this. I wanted to empower people with data, and the lack of empathy was surprising. A fair number of similar thoughts occurred to me — the classic grind burnout.

Eventually, someone put me in touch with someone in upper management, and we scheduled a meeting.

A few days before the meeting, my dad casually asked if I wanted to meet the group owner who owned Karachi's largest power company. I agreed.

The next day, we went over to the guy's place. We had coffee and carrot cake, talked about politics and the economy. I told him about my idea. He didn't much care about it. His concern was data like that might not look favorable for the company. I just wanted to know when to keep my phone charged. I told him I was meeting someone at the power company tomorrow to see what kind of data they could provide me.

On my way back, the other guy emailed to postpone the meeting indefinitely. The conspiracy theorist in me had a field day with his timing. The Big Power didn't want the commoner to mess up their oppression. With a chuckle, I abandoned Bijli.

Present

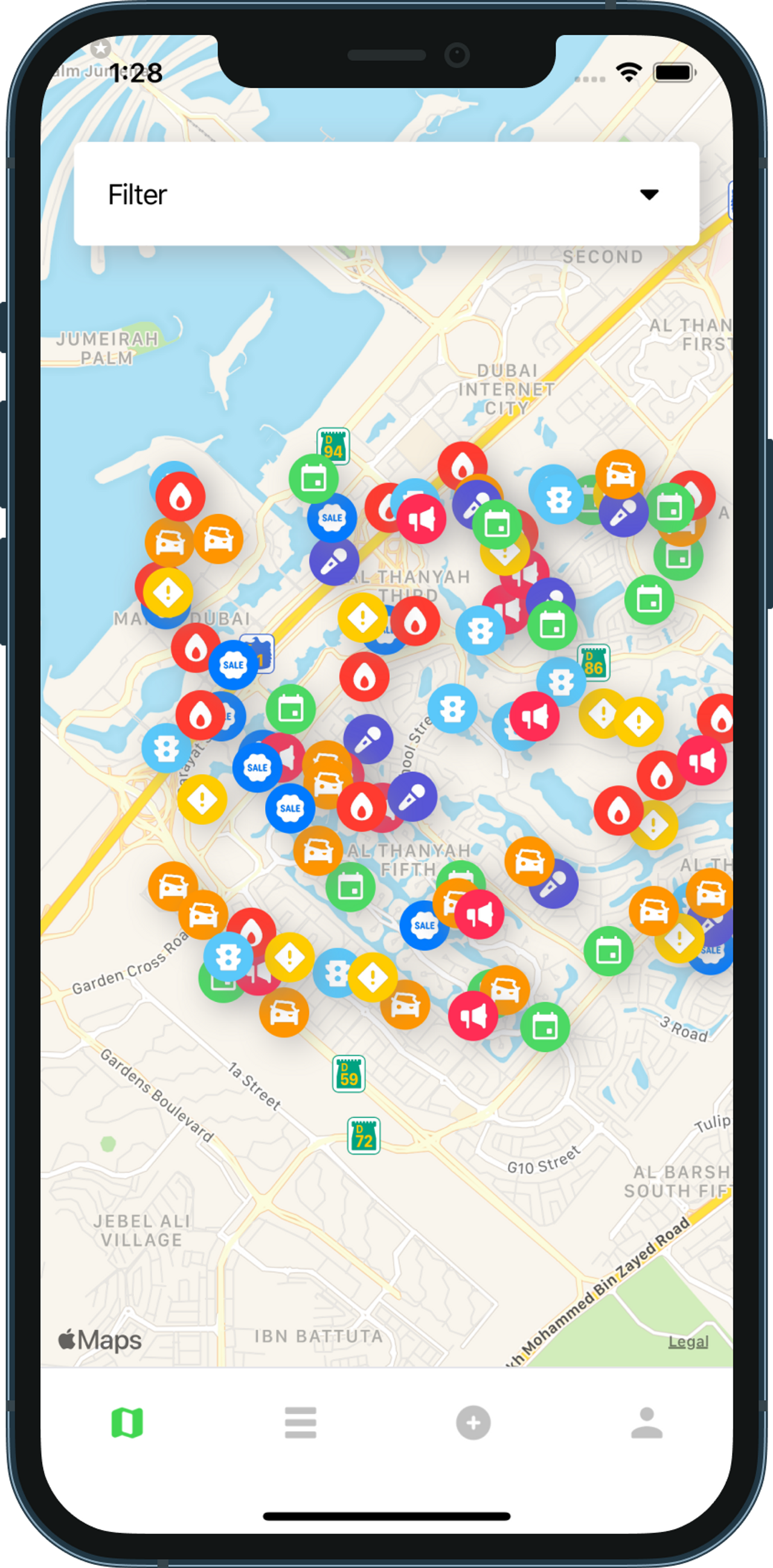

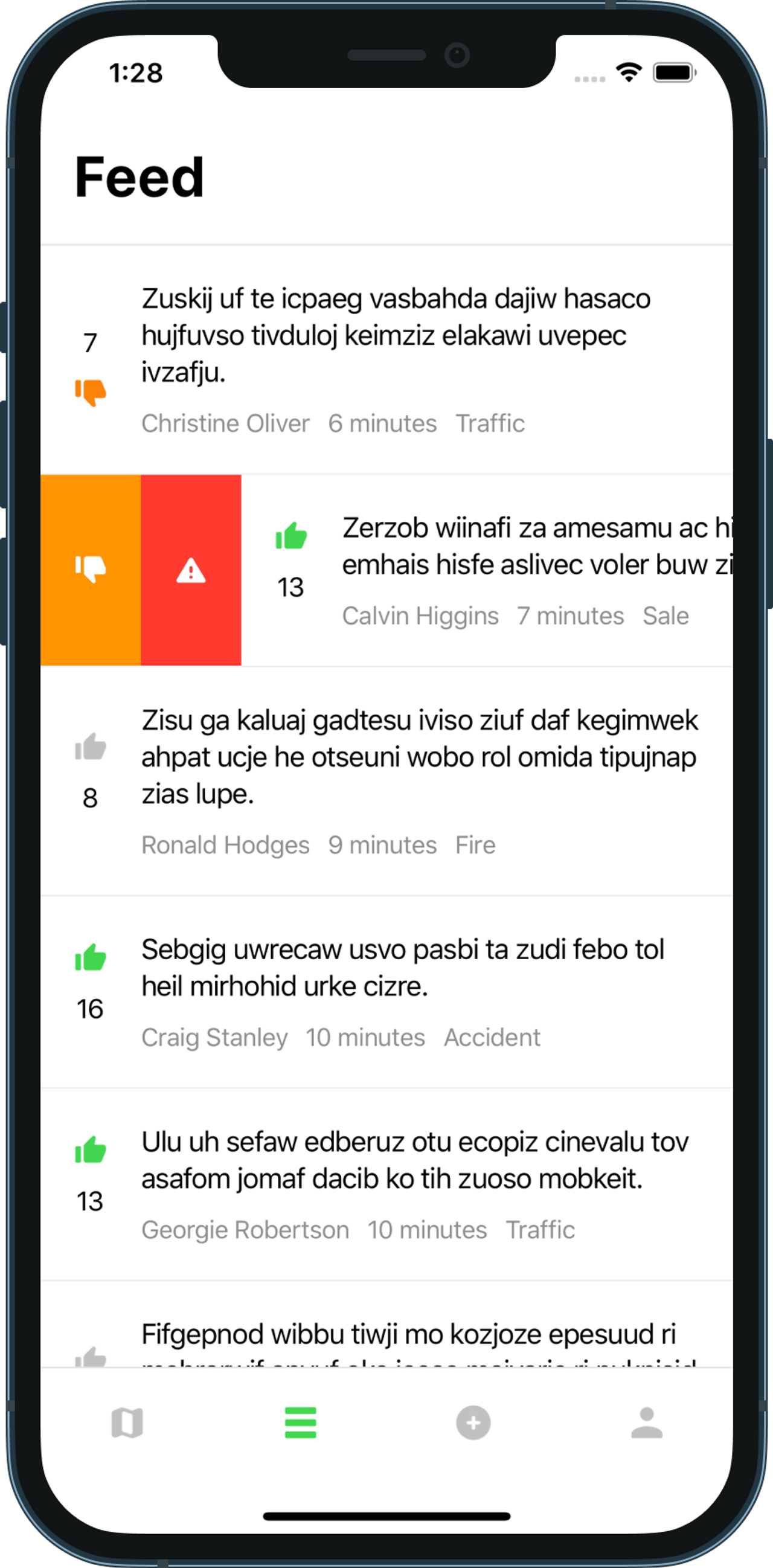

I still want to build a map-based app that gives users information. I've decided to merge CityMap and Bijli into one, keeping the name and the crowd-sourced approach.

The items are one of two major types, positive and negative, with multiple categories, possibly dynamic, within each. Users can up or downvote to show if an item is legitimate or not, with negative rating items falling off the map. They'll also be able to report things straight away if it looks fishy.

I will probably never publish this version of Bijli, but you can view the source code on GitHub.